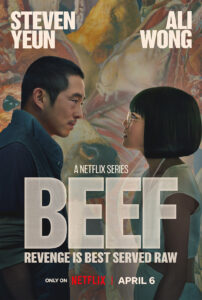

“Beef,” a Netflix series created by Lee Sung Jin, is a show that’s more sophisticated than I had expected. The story follows Danny Cho (Steven Yeun) and Ami Lau (Ali Wong), two Asian-American California residents who get into a road rage altercation, which incites the titular conflict.

The fundamentals of the show are all fantastic. It’s well-written and conceptualized, with some interesting directing choices scattered throughout. Yeun and Wong absolutely kick ass through the whole thing, and both of them deserve Emmy nods for their performances. I’ve never seen better portrayals of the kind of petty tyrants that populate urban America.

The plot is surprisingly intricate, their rivalry motivates infidelity, arson, espionage, theft, stalking and juvenile acts of vandalism. Early in the show, Cho gets revenge on Lau by urinating on her living room floor.

The show is very progressive. Not in a political sense, but more so in its construction. Representation is clearly at the forefront, with all but a couple of speaking roles being played by Asian actors. Certain plot points involve social media and internet scams and there are mentions of side hustles like investing and Bitcoin. Lau is a super-mom, girl-boss type whose husband is an artist that benefits heavily from nepotism. Cho is the owner of an independent construction business who lives in a motel with his brother. These are very 21st-century depictions of wealth and poverty, and these circumstances are the central juxtaposition of the show.

As things develop, the moral of the story begins to emerge, and it takes a surprising stance. All of the show’s progressive scaffolding seems to obfuscate conservative themes and messaging.

And when I say “conservative,” I mean “lowercase-C” conservative. I don’t mean Republican or conservative politics — the show has left-wing undertones but nothing explicitly political.

I more so mean traditional, old-fashioned, orthodox, whatever you want to call it. In a recent New York Times interview, Lee Sung Jin said that the show “really is about how hard it is to be alive.” And, while that’s clearly the main theme, I don’t think it says everything. After watching it, I would add a caveat to the end of that summary: it’s about how hard it is to be alive right now.

Cho and Lau drown in the expectations of modernity. They simply can not handle the lives they’ve constructed for themselves. They frequently cave under economic and social pressures and cope with them by giving into bizarre hedonistic and carnal impulses. At one point we see Cho eat four Burger King chicken sandwiches in one sitting and are told later that he does this often. Lau uses a handgun in an… unusual way, using it as an instrument of pleasure rather than pain, if you catch my drift.

Both of them turn to traditional institutions to seek refuge from modernity. Cho devotes himself to his local Korean church, becoming its leader after some time. His newfound morality drives him to turn Isaac (his scammer cousin whom he previously relied on) into the authorities.

Lau sells her business for $10 million and uses her newfound financial security to spend more time with her family. We’re explicitly shown that her motivation for achieving success in business is so that she can spend more time with her daughter — she’s an aspiring stay-at-home mom.

These things don’t last. In fact, this is only the status quo for a single episode, before it all unravels. But I think it’s the most important episode in the season and the one that’s meant to be a breather. It sits us down for a minute and tells us “this is what it’s about.”

The characters escape their feud, but only for a short time, where we see that there is a path forward. It shows us that not everybody is cut out to be different, to be a trailblazer, to shirk off the trappings of the old world and become something new. There’s something to be said for the well-worn path, the road more traveled. There’s a reason why men who are down on their luck join churches and try to make an honest living instead of trying to achieve a vision or make it out of wherever they live. There’s a reason why women are typically tasked with the home and kids and men are tasked with being the breadwinner.

Again, this is “small-C” conservative, it never implies that you have to follow a certain path or that any one way of living is better than another, but it does assert that there’s nothing wrong with conforming in certain ways.

This is only one of many things you can take away from this show, but it’s the element that stuck out to me the most and the most interesting to think about. I don’t know if it’s necessary right now, or if it’s even correct, but I think there’s merit to it. As these traditional lifestyles fall further out of fashion, it might be worthwhile to contemplate their impact.

For questions/comments about this story email the.whit.arts@gmail.com or tweet @TheWhitOnline.